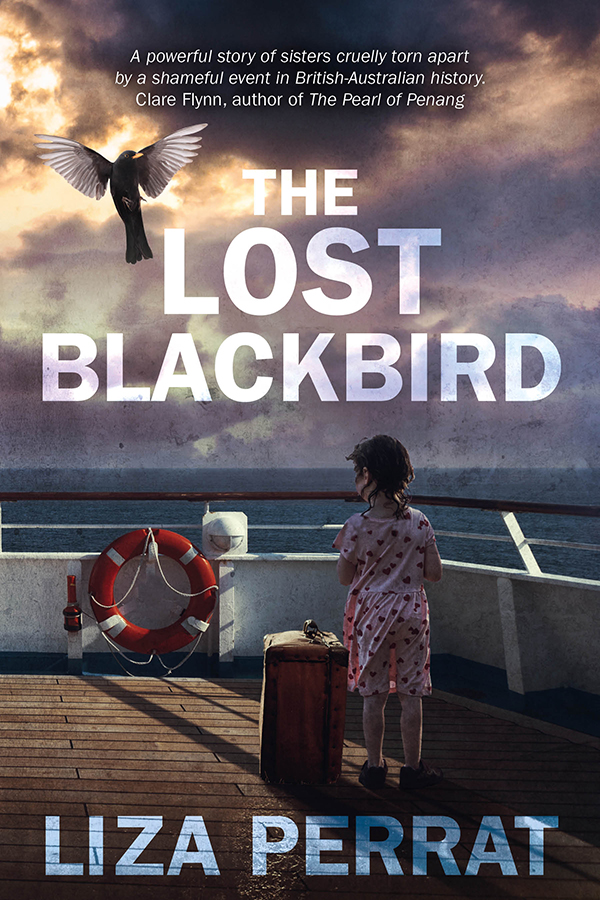

I’m delighted to welcome Liza Perrat back to the blog to mark the publication of her new Australian novel The Lost Blackbird. I was fortunate to be asked by Liza to read the book in advance and contribute a quote to go on the cover. I thoroughly enjoyed the novel and said this “A powerful story of sisters cruelly torn apart by a shameful event in British-Australian history.”

First, something about Liza. She’s a terrific writer and earlier this year was one of the five novelists shortlisted for the Exeter Novel Prize. She’s well qualified to write this book as she grew up in Australia, and worked there as a general nurse and midwife. She has now been living in France for over twenty years, where she works as a part-time medical translator and – of course – as a novelist. She is the author of the French historical The Bone Angel series each of which are well worth reading – The Spirit of Lost Angels set in 18th century France during the Revolution, Wolfsangel – set in Nazi-occupied France and Blood Rose Angel – set during the Black Plague in 14th Century France.

The new book begins in 1962 in London, where the two Rivers sisters, ten-year old Lucy and five year-old Charly are in a miserable children’s home following the (wrongful) imprisonment of their mother for the death of their father. Seizing the opportunity to escape their miserable circumstances with the promise of sunshine and sandy beaches, they are sent to Australia in the now notorious child migrant scheme. Counter to all promises made to them the two sisters are separated on arrival in Sydney, with one going to a caring family and the other to a life of drudgery and near starvation on an outback farm. The book explores their very different experiences as they desperately hope to one day be reunited.

I found Liza’s descriptions of the outback leapt straight off the page – vividly capturing the sights, smells and sounds of the countryside. The portrayal of the two sisters and their very different fates is poignant and engaging. My awareness of the child migrant scheme extended only to having seen the film Oranges and Sunshine which is about the efforts to right the wrongs decades later – so this book being very much about the lived experience of the young sisters was a perfect complement to that.

Liza has very kindly offered my readers the chance to read an extract from The Lost Blackbird – so over to her for that.

Extract from The Lost Blackbird

Chapter 1 –London East End, January 1962

The girl’s father lurches from the flat out onto the landing, where his little girl is playing.

‘Bleedin’ toys,’ he slurs.

At the sound of his voice, she jolts, the breath snaring in her chest. So captivated by her toy blackbird, turning the key on its underside to make it chirp, flap its wings and bob its tail, she’d not even heard him come stumbling onto the landing.

Her father jabs a finger at the wooden toy she now clutches to her chest. He falters, almost topples down the stairs, grabs the railing, steadies himself. She knows it’s the drink that makes him wobbly.

‘Bloody kid,’ he says, ‘always leaving yer stuff lyin’ around … want me to trip over yer toys and kill meself on them stairs, eh?’

He looms, a monster’s shadow, over his daughter hunched on the top step.

‘I didn’t leave my blackbirdie lyin’ —’ she starts, little fingers clenched around her beloved toy. But the rest of her words snag in her throat as her father bends down, jerks the toy from her grip.

‘No!’ She stretches up for it but he holds the bird too high. And the flash from his eyes-on-fire look ripples a fearful quake through her.

The little girl has never owned anything as precious as the blackbird, a present from one of the old people her mother looks after at nights, an ancient man who’d carved it from wood.

It’s the only real present she’s ever been given, this most beautiful bird in the world.

‘Please give back my blackbirdie,’ she sobs, but her father ignores the pleas, waves the toy above her head.

‘Stop yer grizzlin’, girl.’

She cries more.

Lips creasing into a nasty smirk, he flings the bird against the wall.

It clangs like her mother’s favourite teacup with the tiny roses all over it.

But Mum’s out at the shops. Please come home now.

The shock steals her breath. She struggles to get air in and out of her tight chest. Tears sting her eyes as she gazes at her precious bird lying on the ground, its neck twisted, both feet and one wing broken off.

Her father jerks towards the toy. Lifts a heavy boot, stamps it down. Grinds until the blackbird is squashed. All flat. Dead.

The girl knows she should keep still, quiet, but can’t help herself.

‘Why you broke my birdie?’

‘Teach yer not to leave stuff lyin’ around for me to trip over.’ His spittle sprays her brow.

‘But I didn’t —’

Her words are drowned again as he lunges at her, palm flat, taut, hair a dark tangle of wires sticking out of his head. Wiggly lines criss-crossing a purple nose. Herring-breath, mixed with what her mum calls the “whisky stink”, rushes at her in the sweep of his raised arm.

‘Enough of yer lip or you’ll get a beltin’ you won’t forget.’

And when he sways, grabs the rail again, angry face close to hers, the girl knows she has to leap away. Right now!

Younger, steadier, agile, she moves far quicker than he does.

His single shriek springs back from the concrete walls as his head clunks against the stair railing. And down he goes, thudding on each step. Eyes wide, staring. No more scary.

The little girl’s heartbeat thrums against her chest as she stands on that top step, panting hard, watching her father bounce and roll. Bounce, roll, bounce, roll, all the way to the bottom, where he has to stop since there are no more stairs, only the doorway to the courtyard that divides the blocks of flats: North, South, East, West.

The stairwell falls silent. The girl looks down at him, his top half sprawled almost across the doorway, legs splayed backwards, upwards. Angles she’s never seen before.

And in those seconds, the five-year-old’s heart no longer beats at all. The blood inside her turns icier than the January dusk outside. She can’t move; can’t speak. Can only stare down at her father’s unmoving body.

***

From inside the flat, the girl’s big sister also listens to the silence.

She heard their father staggering about the landing, flinched at his shouts and curses; knew Mum would be counting on her to go out there and defend her little sister. But she couldn’t. Just this once she could not face him again.

She cowered behind the closed door, eyes still sore and swollen, cheek still red and stinging from the belting he’d given her before he’d lurched outside and started having a go at her sister.

But silently, she willed her younger sister to shut her trap.

Shush, don’t make him angry.

She opens the door now, slowly, glimpses his body lying at the bottom of the steps and stares in horror at the dark halo widening around her father’s head.

She grabs her sister’s hand and together they sit on the top step and wait for their mother to get back from the shops.

***

The girls’ mother skitters into view on the ground floor. She almost trips over the twisted body of her husband.

‘Albert!’ She drops her shopping bag, slaps a palm over her gasp, gaze resting on the ragged circle of blood around his head. She jumps backwards so no blood seeps beneath her shoes.

Annie Rivers doesn’t bend down to check whether Albert Rivers is still alive, or dead. She turns her head, looks up at her girls sitting on the top step. ‘What the bleedin’ hell happened?’

‘Dad got too much of the drink in him again,’ her older daughter calls down.

‘He broked my birdie,’ the little one sobs.

Their mother is quiet for a moment, listening to her daughter’s small, fragile voice echoing down the stairwell. Shocked, surprised, because Albert’s so big compared with her.

How is it even possible?

But yes, she supposes that with the booze already making Albert unsteady, it is possible.

She picks up her shopping bag and without another glance at Albert’s bloodied head, the awkwardly-angled legs, she steps over him and hurries up to her girls.

She sits on the top step between them, clamps an arm around each girl’s shoulder. Tries not to dig her fingernails through the threadbare clothes into their skin. But she presses a little, needs them to listen.

‘Right, don’t you girls say nothin’ to no one, nobody must ever know what really ’appened, alright?’

She takes a breath, gives the younger girl a long stare. ‘But if anybody does ask, the pair of you are to say it was an accident.’

****

Wishing Liza the best of luck with the new book.

To buy a copy of The Lost Blackbird as an E-book: mybook.to/TheLostBlackbird and it’s also available in paperback .

To find out more about Liza visit her website where you can sign up for her newsletter and get a free copy of her award-winning collection of Australian short stories, Friends and Other Strangers.

0 Comments