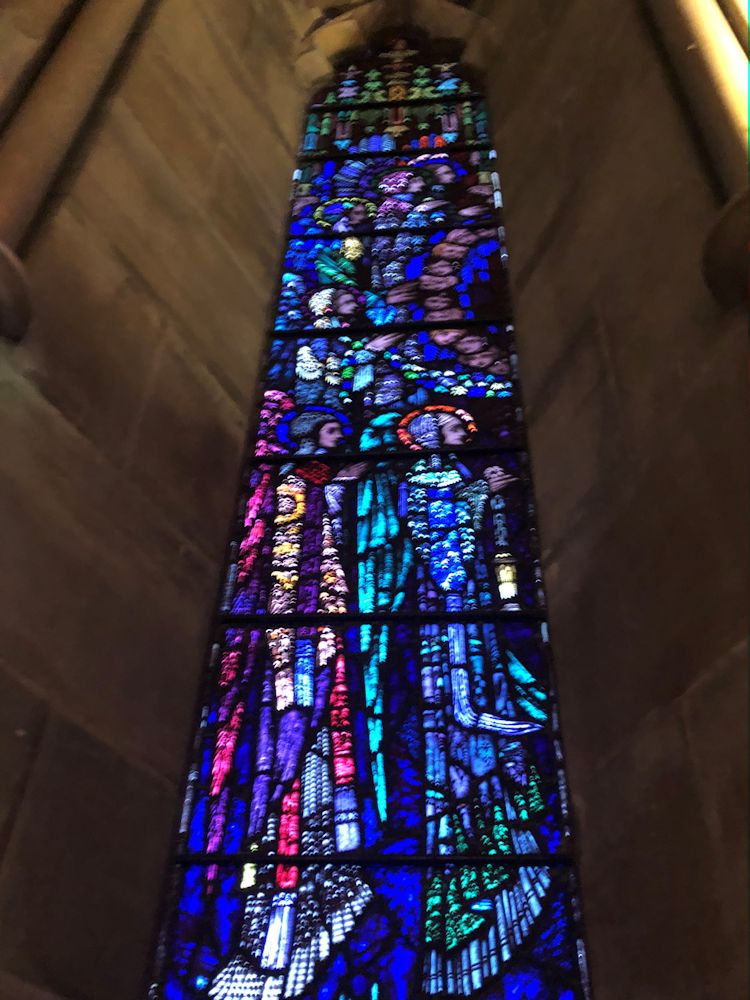

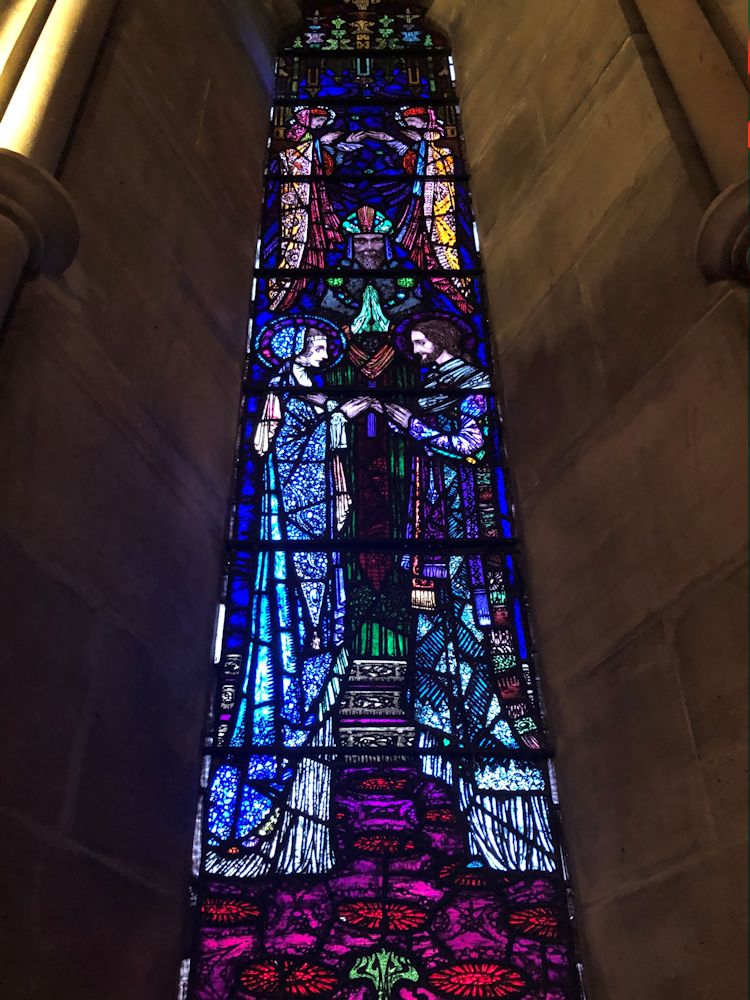

Inspiration: The Irish stained glass window artist, Harry Clarke

My friend Lorna Fergusson who runs the Fiction Fire writing consultancy (and edited Jasmine in Paris) saw me struggling with putting fingers to keyboard when we were on our November writing retreat. Lorna suggested I try a writing prompt. She pulled a couple of ancient books off the shelf at Goddards where we were staying and opened them on random pages. This is what she read out to me:

“Mrs Bowyer, a breathless fussy, little woman”

“Stained glass”

“Albert Dock, Liverpool”

and “Norwich cathedral”

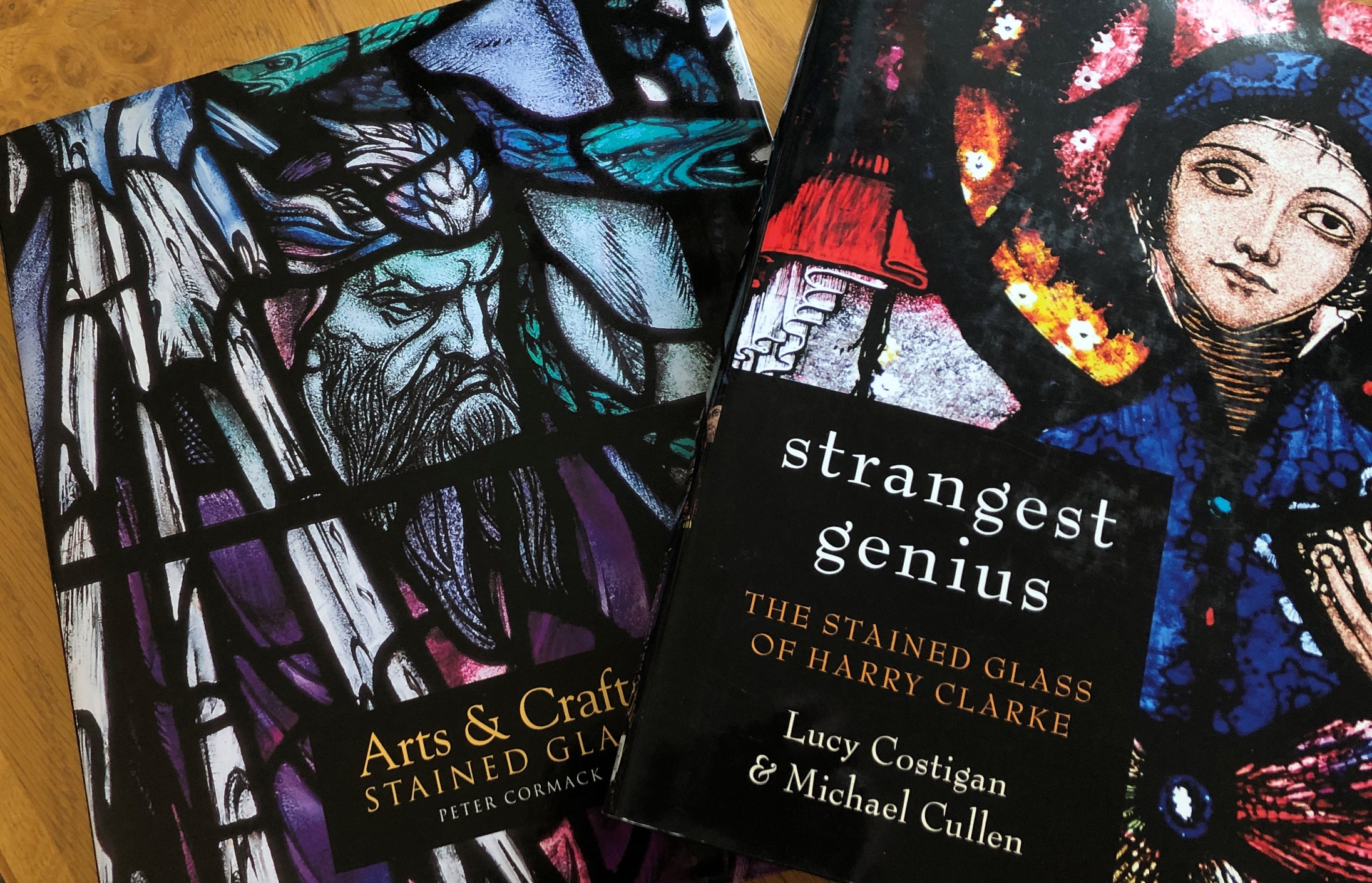

I immediately set aside Albert Dock as I’ve already written three books and a short story featuring the Liverpool docks. But fussy Mrs Bowyer and the stained glass remained – as did the idea of churches if not specifically Norwich Cathedral.. As soon as I got home, I invested in these magnificent and lavishly illustrated books and immersed myself in stained glass. I was hooked.

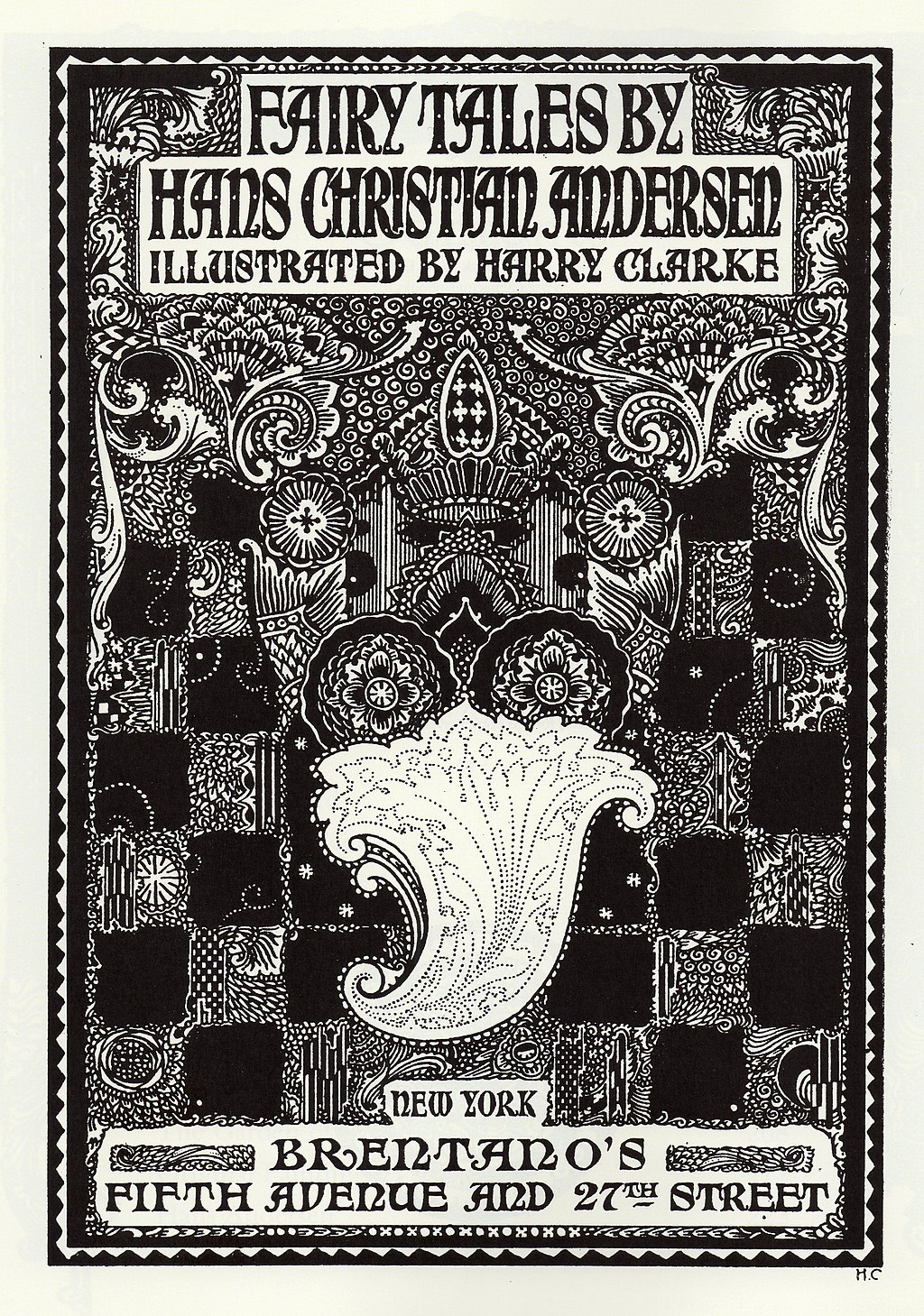

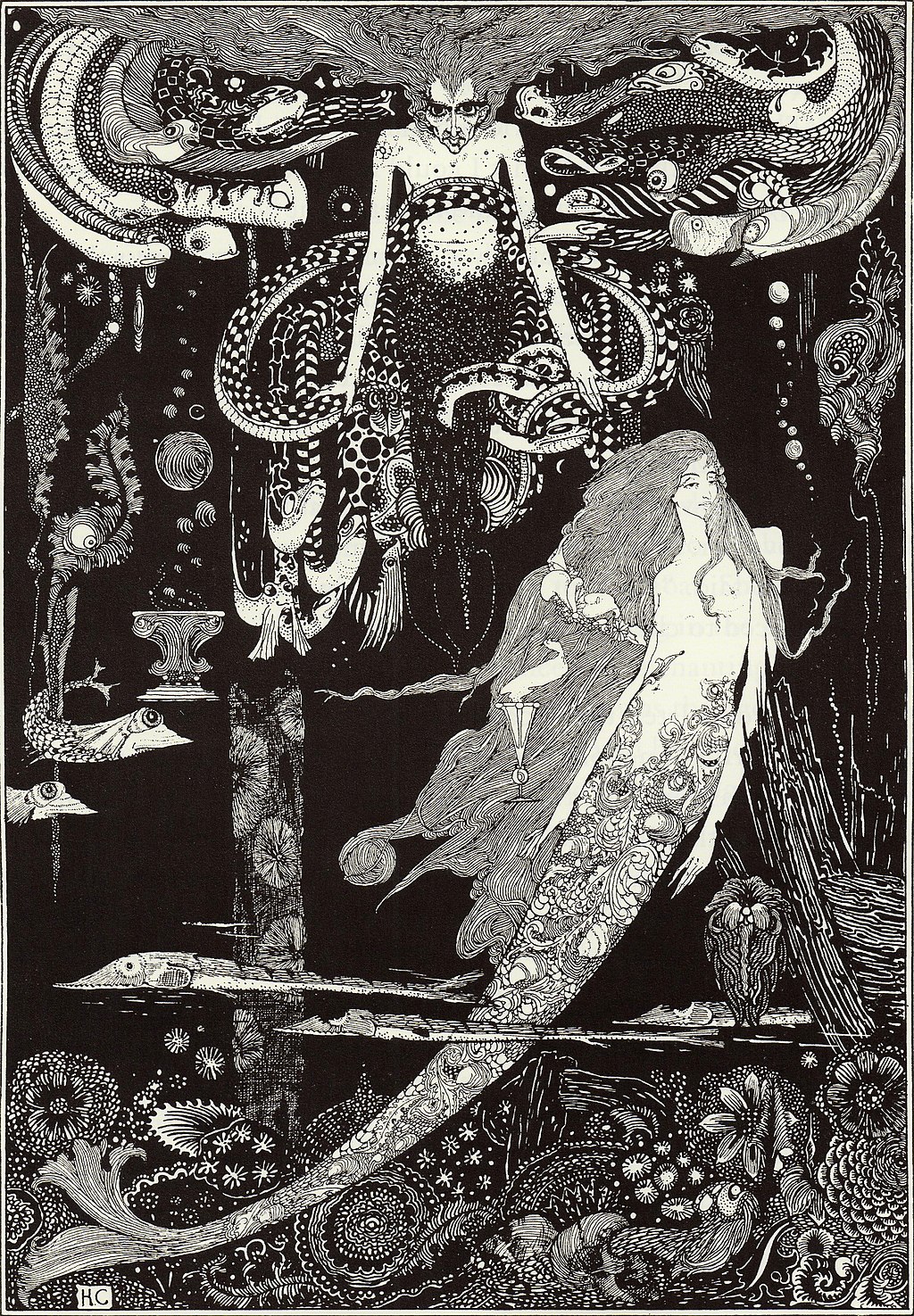

Images: Harry Clarke, Wikimedia; Fairy Tales and Little Mermaid, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The stained-glass artist of my yet-to-be-written book is not Harry Clarke. I am not writing a biography but a work of fiction. Harry is one of several sources of inspiration for my Arts & Crafts window man. But looking closely at Harry’s work – and that of other acclaimed artists will fuel my imagination for my own character – Edmund Cutler. My Edmund is from London and was born a little earlier than Harry – in 1884. And that’s all I’m ready to reveal right now.

0 Comments