A Day out in Ditchling

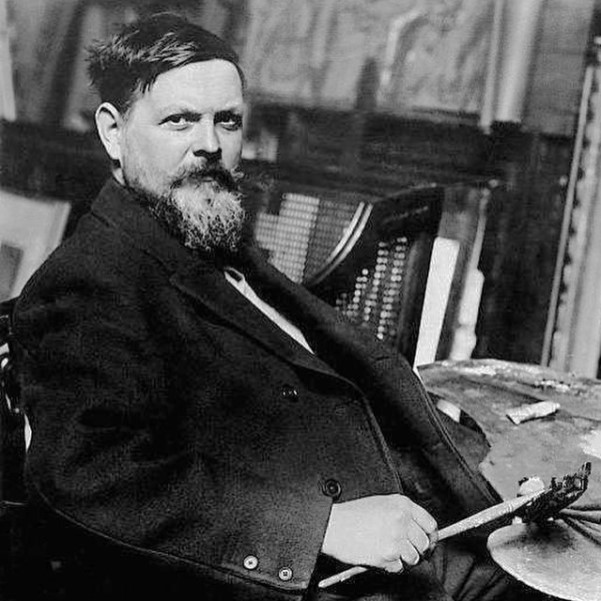

I can’t believe I’ve never been to Ditchling before. Less than twenty miles from me, it used to be home to artist Frank Brangwyn, and notorious sculptor Eric Gill, as well as several brilliant weavers.

The pretty Downland village hosts the Museum of Art & Craft – currently with a fascinating exhibition on weaving, with pride of place to a lesbian couple, Hilary Bourne (1909 – 2004) and Barbara Allen (1903 – 1972), whose work was hung in The Festival Hall for the Festival of Britain in 1948.

In this photo of the hanging, you can see a small black & white image of the late Queen – then Princess Elizabeth standing in front of it.

Eric Gill is notorious enough for his predatory, incestuous sexual deviancy without me going into that here.

One of the greatest sculptors of the 20th C, his work adorns the BBC and numerous other public buildings and his typefaces are beautiful. So awful that a man of such talent had such a dark soul.

Frank Brangwyn was largely self-taught but also worked for a while in the studio of William Morris. Famed for his magnificent painted murals, among his many works Brangwyn even made some designs for stained glass. I was devastated to discover that I had missed an exhibition of his Skinner’s Hall murals at the Ditchling Museum last year. He lived his later years as a recluse in Ditchling, where he died in 1956 at his unusually named house, The Jointure. Brangwyn was born and spent his early years in Belgium so not surprisingly devoted a lot of his energies during the First World War to propaganda paintings and posters to support the war effort.

In The Artist’s Wife there’s a scene where my character Edmund travels by train and is surrounded by propaganda posters – similar in nature to some that Brangwyn produced:

Edmund huddled, collar turned up against a cold wind on the station platform. Behind him, the walls were plastered with army recruitment posters. An image of women and children fleeing a burning village was captioned Remember Belgium! As he waited for the train, he read another on the same theme. This one pulled no punches, showing a German soldier, bloodied bayonet in his hands, trampling on a young woman’s body and about to stamp on her small baby. Edmund read the accompanying text with a growing sense of nausea as it graphically described young girls horribly mutilated, old men burnt to death, mothers and their babies butchered. Here in this small Hampshire town, it was hard to credit that such brutalities were taking place just across the English Channel. His thoughts turned to Lottie. Were innocent children like her really being murdered so cruelly and savagely by the German army?

Ditchling has a beautiful church – not dissimilar to the one I describe in The Artist’s Apprentice and coincidentally also called St Margaret.

Here I am in front of it – and this is my description of Alice seeing the church for the first time:

‘The stone-built church appeared to be very old, but the squat tower topped with a small spire was likely a more recent addition.’

And the same church in The Artist’s Wife:

‘Here in this quiet country church, he was calmer. Comforted. Not by the presence of God or religion. Rather the sense of some ancient truth and beauty in a world that increasingly felt godless.

Perhaps it was in the fabric of the church itself. Here was none of the soaring majesty of York. In St Margaret’s, the columns were simple and stolid. The stone floors dipped where centuries of feet had trodden the surface into curved hollows. The plain glass windows in the body of the church contrasted with the side chapel, which was bathed in the colour and light of the window Edmund and Alice had created in memory of Commander Bowyer.’

St Margaret’s in Ditchling has some stained-glass windows, but like the church in my imaginary Hampshire village of Little Badgerton, they are mostly plain.

0 Comments