Guest blog: The Bookseller’s Wife by Jane Davis

In this special guest blog my good friend and fellow writer Jane Davis introduces her latest novel, The Bookseller’s Wife. Over to you, Jane…

Moorfields and Chiswell Street, 1780

Although most Londoners live within walking distance of open countryside, Moorfields is one of the last pieces of open land in the city, which has breached the confines of its ancient Roman wall to become the largest city in Europe. Before the Great Fire, the fields were where the wealthy took their leisure. Afterwards, they became home to some of the 100,000 people who were left destitute, a shanty town of ‘miserable huts and hovels’ built from wood salvaged from the wreckage of elegant homes. Many chose to settle in the area, a warren of small streets, lanes, alleys and courts. A handful of huts and makeshift shops still remain.

On Mondays London’s maids use the fields to peg out their laundry to dry. They are the site of sporadic open-air markets, shows, auctions, and wrestling. But after dark Moorfields is downright dangerous, with a reputation for harbouring highwaymen and others on the run from the law.

***

“As they pass by London’s crumbling Roman wall, Dorcas touches the stone, a habit which helps her feel a connection with those descendants of Troy who wrote of Brittia as a mythical place. Until a decade ago, here stood Moorgate, built so that Londoners might access the fields for their recreation and the militia could pass on their way to the Royal Artillery Ground. They are now ‘without,’ as it’s called. Beyond Peerless Pond (called Perilous Pond for the number of lives it has claimed), the view expands further, taking in Moorfields, a large, grassed quadrangle that belongs to the people. At its far reaches are ramshackle hovels, built from charred wood and rotten boats those the Great Fire left destitute dragged from the Thames. Though much repaired, their boards replaced, they remain occupied. London is, and always has been, a city of stark contrasts.”

***

Perhaps because there is no shortage of sinners, it became the favourite haunt of open-air preachers. At five in the morning and seven in the evening, John Wesley used to attract crowds of up to 50,000 people. Here in Moorfields his men raised a large shed they called The Tabernacle for use as a chapel. He has since moved into what was a Foundry for casting brass cannons.

To the west of upper Moorfields lies Chiswell Street, home to several notable enterprises and occupants. The Dance family of architects live here. George Dance jr. set off on his Grand Tour aged 17 and then studied architecture in Rome, returning to London with a gold medal for his neoclassical design for a Public Gallery. There are rumours afoot that he has designs on Moorfields, talk that those who have for the last century called it home and traded under the free heavens will be evicted to make way for a handsome quadrangle of brick-built houses. Just what London needs, more luxury housing! Where is the working man to live, I ask you?

At number 26 is Caslon’s Type Foundry. The late William Caslon first turned his attention to type-founding when the Christian Knowledge Society engaged him to make Arabic type fonts for printing the Psalms and New Testament in that language. Soon, the excellence of Caslon’s hand-cut punches drove Dutch type fonts from the English market. Now the motto of English publishers is ‘If in doubt, use Caslon.’ His wife Elizabeth worked alongside him. Now widowed, she runs the foundry as Elizabeth Caslon & Sons and ships her husband’s fonts the world over.

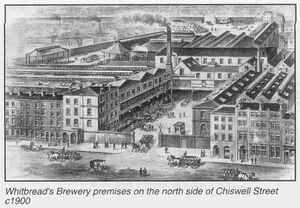

A little further down the road us Whitbread’s brewery. Samuel Whitbread took as his motto: ‘From small beginnings and with fair and honest dealings.’ With this he’s become the largest producer of beer in all of London – and Londoners drink a lot of beer. The water will make you ill. Yet he’s something of an odd-ball, appearing at the Corn Exchange in plain clothes and a white apron. The sight of his shire-horses pulling waggons of beer around the city is a familiar one. His dray horses could raise and lower barrels without instruction. Whitbread’s is famed for its porter and stout, which takes time to mature and that means storage. A great building project is underway that will guarantee Whitbread’s status as one of the wonders of industry. The roof of his new fermenting room will measure 60 feet across and 165 feet long, larger than Westminster Palace.

And in Whitbread’s shadow at number 46 is James Lackington’s shop. Curious fellow, Lackington. He came to London as a shoemaker but soon decided to branch out. I should warn you, the man can talk!

The scene is set. Here is where our story begins.

Excerpt from The Bookseller’s Wife

“And what is your line of business, Mr Lackington?”

“We also have a shop.” Mr Lackington says this as if it sets him on a familiar and equal footing, a presumption Dorcas’s father won’t appreciate. “I’m a shoemaker. Ladies’ silk shoes are my specialism, but I also work in leather. That said…” He looks to his wife as if seeking permission. “We are branching out.”

“Into books,” gushes Mrs Lackington.

Given her reaction to the merest mention of novels, the announcement takes Dorcas aback. “You’re booksellers?”

“We are but minnows in the world of bookselling. But,” Mr Lackington shrugs in an approximation of modesty, “I have hopes.”

Mrs Lackington’s glance at her husband is full of pride, but Samuel Turton lifts the pitcher of ale, and raises his eyebrows in challenge. “That you’ll become a bookseller who occasionally makes shoes?”

Instead of rising to the provocation, Mr Lackington laughs heartily as he slides forward his glass. “I know what you’re thinking, Mr Turton. Sutor, ne ultra crepidam.”

Dorcas feels curiosity awakening, something she has not experienced since the days before supper guests became a rarity. “You speak Latin?”

“Alas, that’s my only scrap, and I’m not altogether sure my recall is correct.”

“Your recall is always correct.” His wife’s protest is proud and indulgent. “Old ladies of our neighbourhood considered my husband a child prodigy because he could recite several chapters of the New Testament,” she says. “Even now, he only needs to read something once, and he can say it right back to you.”

As she talks about him, Mr Lackington reaches for his wife’s upper arm and gives it a light squeeze. “Let us ask Miss Turton.” He leans towards Dorcas. “Did I have it correct?”

“Sutor, ne ultra crepidam. Shoemaker, not beyond the shoe.”

“There you have it!” he exclaims, delighted. “With a little word in Saint Crispin’s ear, a shoemaker may become Lord Mayor of London, or he may become a bookseller.”

More about The Bookseller’s Wife

London, 1775: The only surviving child of six, Dorcas Turton should have been heiress to a powerful family name. But after her mother’s untimely death, she is stunned by the discovery that her father’s compulsive gambling has brought them close to ruin. With the threat of debtor’s prison looming large, she must employ all her ingenuity to keep their creditors at bay.

Fortunately, ingenuity is something Dorcas is not short of. An avid reader, novels have taught her the lessons her governess failed to. Forsaking hopes of marriage and children, she opens a day-school for girls. But unbeknown to Dorcas, her father has not given up his extravagant ways. When bailiffs come pounding on the door, their only option is to take in lodgers.

The arrival of larger-than-life James Lackington and his wife Nancy breathes new life into the diminished household. Mr Lackington aspires to be a bookseller, and what James Lackington sets out to do, he tends to achieve. Soon Dorcas discovers she is not only guilty of envying Mrs Lackington her strong simple faith and adaptable nature. Loath though she is to admit it, she begins to envy her Mr Lackington…

0 Comments