Sorry about the rather gruesome looking set of choppers, but I visited the British Dental Museum the other day. I’d been really looking forward to it – I needed to get a feel for what having false teeth would have been like in the late nineteenth century. Sadly it was a bit of a let down.

It’s not that there weren’t interesting exhibits – they had some – but calling it a museum is perhaps stretching credibility. It was the size of a small living room.

It was half term and I had my thirteen year old nephew with me. He was up for seeing some gory stuff and finding out all about what it must have been like in the bad old days if you got toothache. Sadly he found little to get his own teeth into. There seemed to be no apparent order in the way items were displayed – no chronology or evident grouping by topic – although there were only five or six display cabinets to look at anyway. It all struck me as a bit of a missed opportunity. Quite honestly I had already found out more information online than I did there. And the annoying thing was we had trekked into central London in the pouring rain.

So what did we learn? That hippopotamus and walrus ivory was the most common material for making denture bases and then real front teeth were secured to the base with gold pins. In Britain these were often known as Waterloo Teeth – as the battlefields were a plentiful source for sound teeth from the mouths of dead soldiers. I already knew this – my character, Eliza, gets fitted with a set of Civil War Teeth – as she is in America – but my nephew did make some suitable groaning noises at the prospect. If there were no dead soldiers to supply your new pearlies, you had to rely on your friendly neighbourhood grave robber. Both the ivory and dead people’s teeth were highly prone to decay.

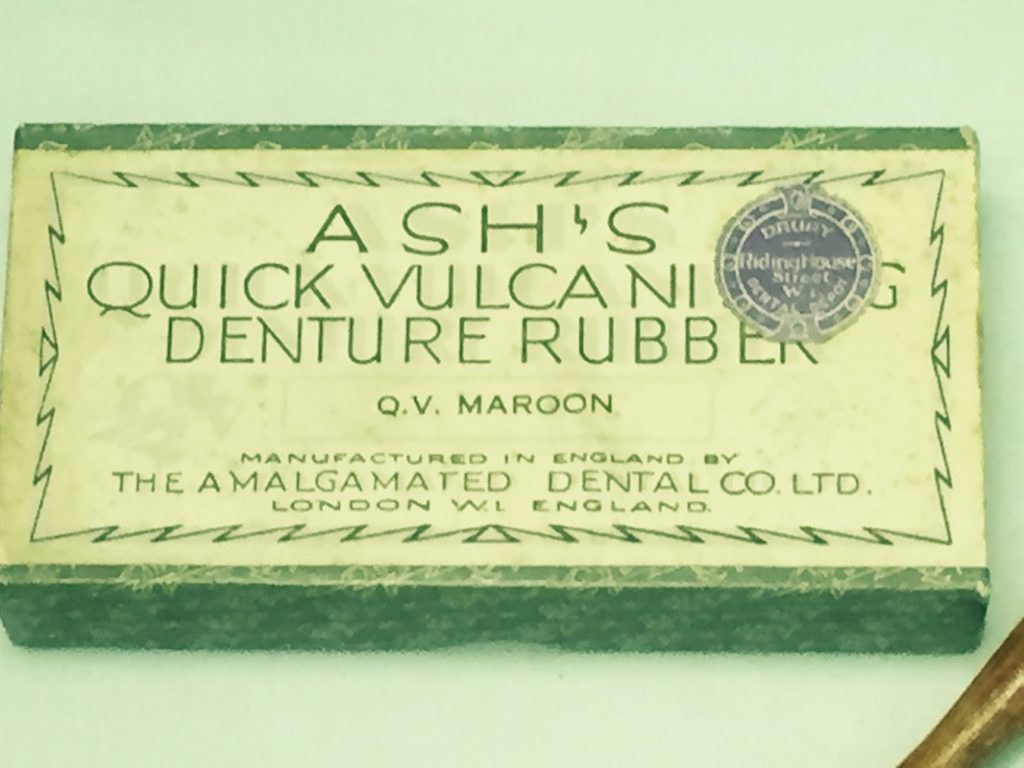

Eventually ivory was replaced with vulcanite as the denture base of choice, allowing for hinged articulation between jaws. Porcelain teeth were mounted in wax, shaped to represent the required denture. These were then embedded in Plaster of Paris inside a gunmetal flask to form a mould, with hot water used to wash away the wax, leaving the porcelain teeth, and the resulting cavity packed with softened pieces of rubber. The flask was then heated at 170ºC in a vulcaniser. After the process is done the denture was trimmed, polished and fitted.

Of course getting fitted for dentures was quite an advanced procedure. Most of the time dentistry used to consist of some bloke (often a blacksmith or a barber) yanking your painful infected tooth out with a pair of pliers.

Apparently the museum has a collection of around 30,000 items including dental related paintings. It’s a shame it doesn’t dedicate more space to displaying it.

0 Comments