My first novel, A Greater World, begins in a place I have never actually visited. At least not the exact location, although I do know the surrounding area from my time living in the North East of England. The book originally opened with Elizabeth Morton, the main character and her sister, but I did a bit of pre-publication switching. When I wrote their chapter I didn’t yet know who my main male character was going to be.

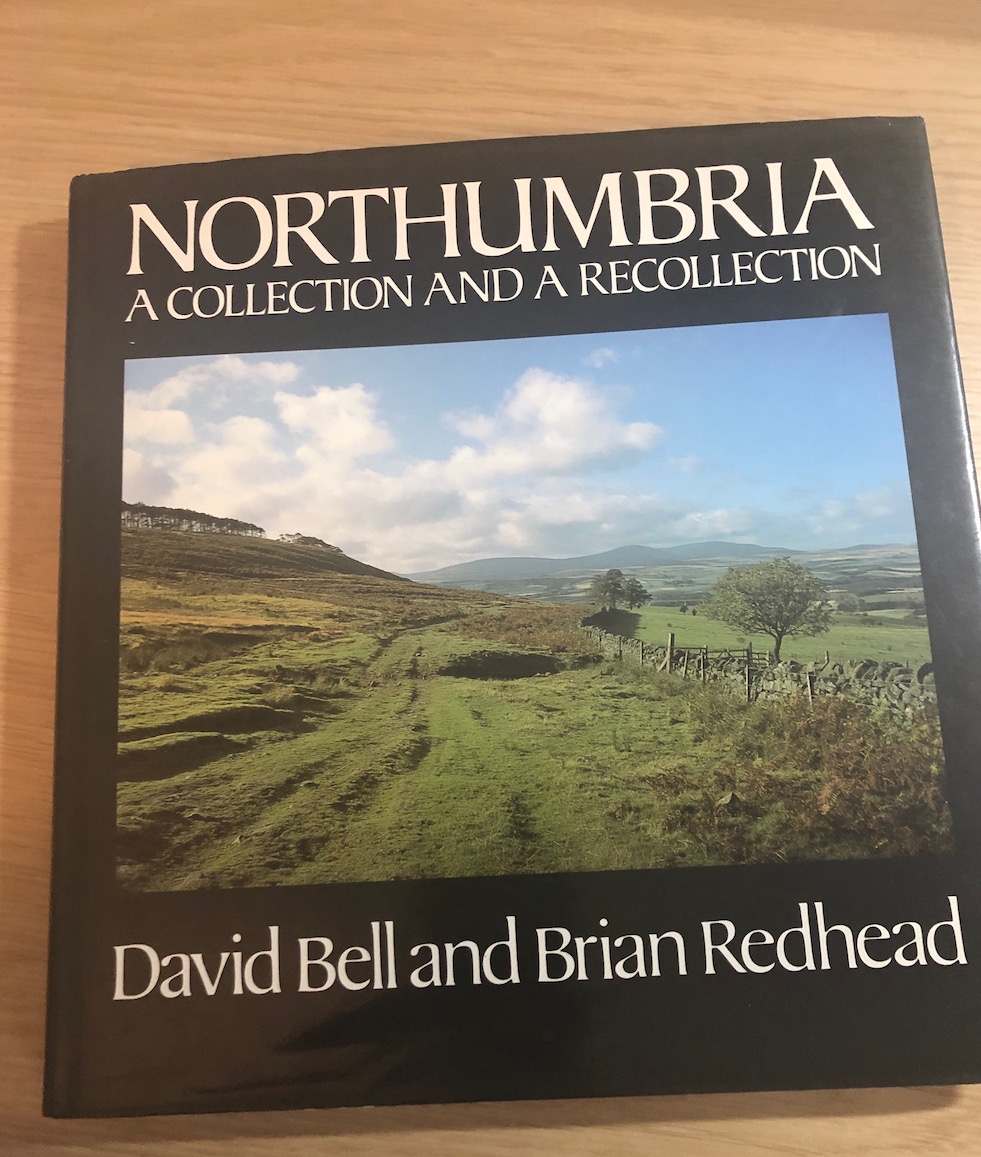

The inspiration for Michael Winterbourne came from a book – a picture book on Northumbria, a gift from dear friends when I left Newcastle over thirty years ago to live and work in Paris. The gorgeous photographs were by David Bell (my copy is signed by him) and the commentary was by Brian Redhead. During my struggles to come up with a male protagonist I believed in, I happened to take Northumbria A Collection and A Recollection off the shelf while I was having a cup of coffee. On page 179 was a photograph of some lead miners’ cottages in Upper Weardale, near Nenthead. There are two adjoining rows of three cottages at right angles to each other and nestled in the valley. As soon as I saw the image, Michael Winterbourne came to me. I knew these cottages were where he lived. Until that point I had no idea that he was even a lead miner, nor that he had survived the First World War. Looking at the picture (above) Michael came to life for me. I immediately could see him, his younger brother Danny and their parents, living in that conjoined cottage which seemed to huddle against the side of the dale, as if sheltering from the elements.

I wanted to be able to share the image here on the blog, so I contacted the old friends who had given me the book. It turns out that David Bell had owned a bookshop on Gosforth High Street and they knew him. My friend hadn’t seen him in ages but was glad of the chance to have an excuse to contact him. Sadly, it turns out he died in 2018. My friend put me in touch with his wife, Rosemary, who was delighted to hear that his photograph had inspired my character and kindly granted me permission to use it in this piece.

A personal tragedy hits Michael at the beginning of the book when he accidentally kills his younger brother. Here is an extract:

Danny was beginning to irritate him with his endless chatter. Michael knew he would never succeed in teaching his brother to shoot. He himself had learned as a small boy and it was second nature. Even the years serving in the Great War had not put him off. He had been away from the worst of the action on the front line, digging trenches and tunnels with the Engineering corps.

They lay in the rough grass with only a couple of lapwings for company. The black and white crested birds broke the silence of the dale with their distinctive peewit calls. It was hard to believe that under this open and empty landscape was what was once one of the biggest and most profitable lead seams in the world. In their father’s youth there were mines everywhere, but most had long ago given up the last of their lead.

A large jackrabbit emerged from the trees and stopped at the top of the slope. Michael put his finger to his lips and nodded at Danny, then raised the gun and aimed, but as he did so a shaft of sunlight blinded him. He held the gun steady and squeezed the trigger. As the shot rang out he was aware of a sudden movement. Damn – he’d missed the bugger. He wiped the sweat from his brow and raised the gun again. Where had it gone? To the right of where it had been before he sensed movement and fired. He’d get the bastard after all.

He turned to Danny with a grin. The boy liked to race the dog to retrieve the prey. It was a silly game he always played – even though Stone had never lost the contest yet. But Danny wasn’t racing up the hill. Michael looked back at the top of the slope as his heart pounded against his ribcage. Stone was whining. Michael dropped the gun, shaded his eyes with both hands and looked into the blinding sunlight. His brother was in the long grass, arms stretched out in front of him as though trying to grab what was a very dead rabbit.

He screamed Danny’s name and raced up the slope. God, let him be alive. Let him be alive.

Danny was on his stomach, a pool of blood seeping from under his body and a dark hole burnt through the back of his jacket.

Michael turned the boy over and lifted him up. The dog howled as he tried to make Danny stand up. Realising the futility of this, he sank to the ground, cradling his brother in his arms.

‘No! God, no! What’ve I done? I’m sorry. Please, please, wake up! Dan! Don’t die.’

The boy’s face had a puzzled expression: eyes still open wide.

There was no time for any last words, for Michael’s plea for forgiveness to be acknowledged, or the chance to comfort the lad before he died: the bullet had gone straight through his heart. Michael’s guttural cry seared the silence of the dale.

He kicked the rabbit carcass into the trees. The foxes or crows could have it. He lifted Danny and carried him over his shoulder, with Stone trailing behind, the dog’s whimpering an eerie accompaniment.

He walked towards the cottages, his shirt red with his brother’s blood, his arms aching with the weight of the boy. Neighbours came to their doorways and several walked out to meet him. Michael was blind to them.

‘What’s happened? Is he hurt bad?’

‘Let’s help you carry him.’

He ignored them all and staggered on in silence.

Michael knew he would never be able to forget the way his mother looked at her dead child. The boy’s face had a look almost of pleasure and it was hard to believe that his spirit had fled the still-warm body. She began to keen, her voice rising like a banshee as Michael and his father laid the boy on the kitchen table.

‘Danny, Danny! My baby. Me little, lovely lad.’ She turned to Michael. ‘What happened? What did you do?’

Michael looked down at his boots and shook his head. His mother rushed towards him and hammered her fists into his chest.

‘You were meant to look after him. He were just a wee bairn.’

‘It were an accident, Mam – the sun were in me eyes – I didn’t see him move…’ The words sounded lame as they came out of his mouth and he stopped trying to answer.

His father eased her across the room to the bed and made her lie down, then turned to Michael. ‘Son, what the hell possessed you? For God’s sake, man! How did it happen? We trusted you to look out for him.’

He shoved his hand into Michael’s shoulder, but then collapsed back into a chair, his head in his hands and began to sob. Michael had never seen his father cry before.

He left his parents and walked up the hill behind the houses avoiding the scrutiny of the neighbours and their well-intended words of comfort.

No one in the cottage slept that night. Michael’s mother was sobbing, inconsolable, while his father kept a vigil by the body of the dead boy. Michael lay on the bed he had shared with Danny, thinking of the many times he had complained when Danny stole the bedcovers or kicked him during a bad dream. Now the narrow truckle bed felt large and empty.

He could not dispel the image of Danny’s face, with its surprised half smile. Danny had been afraid of the dark and Michael hated the thought of him being shut up in a wooden box and left to rot away under the soil. He thought of all those other men and boys, blown to pieces and left to mingle with the mud in shell holes or their body parts anonymously buried in communal graves. He and Danny had been spared that fate, but right now he would gladly be lying in a grave on the Somme if it meant Danny would be alive.

His father was awake slumped in his chair, staring at the embers of the fire, when Michael rose just before dawn. On the floor beside him was a scattered collection of carrots and parsnips, still lying where he had swept them off the table to accommodate Danny’s corpse.

People often ask where I get my ideas and I am often tempted to reply in the words of Terry Pratchett “There’s this warehouse called Ideas R Us”. Stephen King once said he is only able to identify where his ideas originated about fifty per cent of the time and I think that’s a generous assumption. Most of the time I just sit down at the keyboard and ache my brain. But that simple image of those cottages made sitting at the keyboard a fast and furious session rather than a slow torturous one. I’m sorry I never got the chance to thank David Bell personally.

This starts off so interesting, I can’t wait for you to finish and I can escape to another world. I love reading your books. Thank you.

Thank you! This one is finished. It was my first book. There is also a follow up to it and I am working on a third in the series!